Figure 9: Sarcoma of cecum causing intussusception: resecting tumor, reduce and repair of intussusception in 20-month-old male rat (Tugger).

Case history and photos

History

Tugger (black hooded male rat) was born on approximately, 24 September 2010. He was adopted from a rat rescue on 16 November, along with two cage-mates. He was castrated at 12 weeks of age. His genetic background is unknown.

On the first day of adoption mild upper respiratory noises were noticed and Tugger was taken to Dr. Harvey DVM the following day. He was successfully treated with Baytril, however miscellaneous odd respiratory noises were sporadically heard throughout his life. There were no other signs of illness.

The rat group was housed in a large cage. Layers of plain brown bags were used to cover the cage floor. Eco-bedding was used in the litter boxes. Fleece hammocks provided sleeping areas.

The rats’ diet consisted primarily of Envigo (Formerly Harlan Teklad) 2018 until 6 months of age. From that moment on they were gradually introduced to healthy grains, vegetables, fruits, and fresh protein. As their weight became stable Regal Rat was added to the diet. From 1 year of age they were maintained mostly on Regal Rat and small portions of low fat human foods. Fresh dinosaur kale, dandelion greens, or bok choy were offered nightly. The treats they received consisted of organic oat/rye/barley/wheat/triticale flakes, bits of fruit such as blueberries/grapes/figs, and one dried cranberry at night semi-regularly. Every night fresh distilled water was provided in a water bowl (which was used for both drinking and playing in).

Clinical Signs

On Saturday 26 May 2012, at roughly 20 months of age, Tugger suddenly started showing signs of pain (Note that he had seemed “off” a week earlier, but had appeared to be feeling okay again later). Tugger displayed piloerection (“fluffed up” fur) and lethargy: he remained inside a box, did not move about much, and did not want to play. His keeper checked him for lumps, but could not find any. She was unable to locate a focal point for the pain, but she did notice that Tugger “squinched his sides in”. Tugger was given Ibuprofen, but this did not seem to help. He was then given Metacam, after which he looked “normal” again.

However, the next morning (Sunday) Tugger was again displaying piloerection and he appeared “despondent”. He was eating and drinking, but not enthusiastically. Once again, there were signs of abdominal pain: he was twisting and stretching as he moved about and his abdomen near his haunches looked “pinched-in”. The pain appeared to be getting worse

On Monday morning Tugger did not want to eat or drink, and would not leave his hammock. As the vet’s office was not open today, more Metacam as well as Amoxicillin were able to be obtained temporarily. Tugger appeared somewhat better in the afternoon, after being given the medications. However, he remained extremely subdued and his eyes appeared “glazed and distant”. As his keeper suspected that he was becoming dehydrated, she started syringe-feeding him sugar water with some salt added in, every two hours. In the evening Tugger looked less “fluffed up” and dishevelled, but he continued to twist and contort his body and appeared agitated. When he appeared unable to sit up to eat, he was given a dose of Buprenex. This seemed to soothe him and afterwards he lay calmly in his keepers hands, bruxing. At night he drank some water, but he also started making “monkey noises” (respiratory noises), so he was started on Baytril.

On Tuesday morning Tugger did not show piloerection, was moving about, and was eating small portions of food every now and then. However, he was still stretching and contorting his body and appeared to have difficulty (pain) when sitting up. Tugger was now making soft “monkey noises” almost constantly, which increased when he became stressed, for example when his keeper was about to “force feed” his medications. Tugger’s keeper took time off work to take him by the vet’s office, where a vet tech confirmed that he was dehydrated. Tugger received 10ccs of sub-Q fluids and his keeper was given instructions to repeat this procedure in the evening. An appointment was scheduled with the vet for the following morning. In the evening Tugger ate two teaspoons of “Trader Joe’s Carrot-Ginger soup”, which he liked. However, it resulted in severe diarrhea that lasted three hours and required several baths.

Diagnosis

On Wednesday 30 May Tugger was taken to see Dr. Harvey . She palpated a mass in his lower abdominal area. It was confirmed through X-rays to be “approximately 2.5cm in length, approximately 2.5cm in diameter, and very round in appearance” (quote from Tugger’s keeper). Given the clinical signs it was considered critical to remove the mass as soon as possible and a space was cleared in the schedule to perform exploratory surgery.

Treatment

Below are Dr. Harvey’s notes on the surgical procedure, which took place in the early afternoon of Wednesday 30 May. Tugger was under anesthesia for 75 min. His heart rate remained steady throughout the surgery. He spent two hours recovering in an incubator.

-

Abdominal exploratory for painful mass.

Anesthesia: Premedicated with Butorphanol and atropine, iv catheter place in later tail vein. Metronidazole 2.5 mg slow iv. induction and maintenance with Isoflurane/02 mask.

Surgery: a midline ventral abdominal incision revealed a ceco-colic intussusception caused by an intraluminal mass in the cecum arising from the cecum wall near the apex. The cecum was exteriorized and packed off with laparotomy pads. An incision was made in the cecum to allow eversion of the intussuscepted portion. The tumor and the attached tip of the cecum was sharply excised and then both cecal incisions were closed with 5/0 Vicryl simple interrupted pattern and leak-tested. The excision site failed the first leak test, was oversewn with 5/0 vicryl in a Cushing’s pattern, and then was leak-free. A nearby area of ileum had a 4 mm attenuated area in the wall (pressure necrosis?). This spontaneously ruptured. The rent was sutured with 5/0 vicryl simple interrupted pattern, and leak-tested. The intestine was lavaged 3 times with warm sterile saline. Instruments, gloves and drapes were changed. The abdomen was lavaged with warm saline twice.

Closure:

- The abdomen was closed with 4/0 PDS in a simple continuous pattern.

The subcutaneous layer was closed with 4/0 PDS in a simple interrupted pattern.

The skin was apposed with 4/0 PDS in a continuous subcuticular pattern and 1 drop of skin glue was used to cover the knot.

Recovery was smooth and “Tugger” was discharged on Baytril, metronidazole, and buprenorphine. The original very conservative dose of 0.02 mg/kg buprenorphine was increased to provide better analgesia to 0.04 mg/kg to 0.08 mg/kg transbuccally every 4 to 8 hours. Ileus was not encountered.

Removal of the mass resulted in a decrease in weight by about 30 grams. The mass was sent out for histology (see histopathology report in the Outcome section). Dr. Harvey inspected Tugger for other masses, but did not find any.

Outcome

Tugger’s chance of survival was quoted as being “50-50”. However, if he hadn’t been operated on, he probably would have lived for no more than a couple of days and been in constant severe pain.

Once Tugger woke up, he immediately showed signs of pica (eating paper), presumably due to pain, so his dose of Buprenex was increased. He returned home in the evening, where he was placed in a “hospital cage” with only fleece as bedding material. He ate some baby food and yogurt with blueberries, and drank well. A heating pad was placed underneath a portion of his cage, which he seemed to like. He dozed a lot, alternated with wandering around seemingly searching for paper to eat.

Note that Tugger was not bandaged post-op. The intestinal leakage that had occurred made him susceptible to often fatal infections, so Dr. Harvey wanted Tugger’s keeper to be very alert during the first three days post-op for any leakage from the incision or fluids on the fleece, which could indicate infection, possibly peritonitis, or sepsis.

A histopathology report of the removed mass showed the following:

Biopsy

HISTORY

Three days of abdominal pain. Mass palpated and exploratory surgery performed. Mass in the large

intestine had caused an intussusception. The mass was resected

SPECIMEN

One excisional mass from the cecum

MACROSCOPIC DESCRIPTION

Cecum- Extending from an ulcerated surface and infiltrating transmurally, often obliterating the smooth

muscle wall, is an infiltrative and poorly demarcated neoplasm. Neoplastic cells are present in interlacing fascicles and sheets sometimes separated by a scant amount of collagen. The neoplastic cells have poorly defined margins and are spindloid to polygonal with moderate anisokaryosis. They have open faced nuclei with clumped chromatin, occasional prominent eosinophilic nucleoli and streaming, finely vacuolated, amphiphilic cytoplasm. Mitotic figures range 0-1 I high power field with 6 mitoses counted in ten high power fields. Multinucleated tumor cells are noted. Much of the mucosal surface is ulcerated and replaced by a fibrinosuppurative plaque with adherent bacterial colonies. Multifocally, small numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells with occasional eosinophils infiltrate the intact mucosa. In areas, the submucosa is expanded by edema with similar inflammation surrounding congested blood vessels. These changes along with some spindle cell proliferation in the submucosa extends to the margin of the submitted tissue.

DIAGNOSIS

Cecum -Sarcoma with mucosal ulceration, see comment on margins.

COMMENT

The mass is a transmural sarcoma. The neoplastic cells are pleomorphic with a low to moderate mitotic rate. The underlying histogenesis of the sarcoma is uncertain but possibilities include a fibrosarcoma or leiomyosarcoma. The neoplasm is poorly delineated and infiltrative but in the examined sections it does not extend up to the margin of the submitted tissue. However, there is some submucosal spindle cell proliferation associated with edema and inflammation at the margin of the submitted tissue. While I suspect that this is a reactive change, I cannot completely rule out that there is some extension of neoplastic cells at the margin.

Follow up

The following day Tugger appeared to be in pain: he was agitated and continuously tried to gnaw on his fleece, or groom his keeper when she held him. He did drink well and ate small portions of foods. Note that he had been placed on a low-fiber diet, to reduce stress to his intestines; it consisted of: banana, yogurt, scrambled egg, soft tofu, white rice, baby food, rice milk, and watermelon. He urinated regularly, but did not pass feces.

On the second day post-op Dr. Harvey was consulted regarding Tugger’s pain and the Buprenex dose was increased. In addition, it was given every 5 hours rather than every 6-8 hours, based on his keeper’s observation that his condition seemed to fluctuate between feeling well and not well throughout the day. There were no signs of leaking or infection. In the evening Tugger was allowed a brief visit with his cage-mates, which seemed to excite him and made him become more active. Afterwards – 30 hours after the surgery – he passed feces again for the first time. He no longer displayed his previous intense urge to groom his keeper, or seek out salty fluids. He appeared relaxed and pain-free as he slept. Unfortunately, Tugger’s feeling better resulted in him incessantly bothering his incision site; his keeper distracted him by holding and scritching (type of petting) him until 3am.

On Saturday 2 June, the third day post-op, Tugger was taken back to Dr. Harvey for an inspection of his incision site. She stated that there was some minor fluid build-up, but that this was normal. To everyone’s relief there was no apparent irritation, nor were there any signs of abdominal infection. Unfortunately, the results of the histopathology (see report in the Outcome section) indicated that the excised mass was cancerous. It was unclear whether the margins were clean. Fortunately, the cancer type was slow-growing, so there was a good chance that Tugger had several months left (note that he was around 1yr 8mo old at the time). At his keeper’s request, one of the vet techs placed an “anchor tape bandage” on Tugger, using a slight variation on instructions by Lindsay Pulman LVT. It took two tries to wrap the bandage effectively. Back home, Tugger was not pleased at being bandaged, but he continued to eat and drink. He displayed a desire to remain close to his keeper, so he was placed in a loose “snugglescarf” so that he could be carried around easily.

The next morning, Tugger walked out of his bandage. His keeper assessed that he would no longer bother his incision site, so she did not attempt to re-bandage him.

Tugger’s keeper returned to work on Monday, as his pain seemed under control. During the week he was given brief visits with his cage-mates in the “big cage”, which excited him very much. He clearly wanted more free-range time and became increasingly agitated at being confined to the small hospital cage.

On Tuesday (6th day post-op) Tugger’s keeper palpated his incision area and felt a hard swelling along the entire incision length, as well as a more nodular swelling at the end. During the final checkup on Friday (9th day post-op), by which time the incision had healed, Dr. Harvey explained that there was some fluid build-up and that the end of the suture line was showing some reaction and swelling, but that this was normal and would reabsorb.

On Saturday 9 June (10th day post-op and two weeks after the clinical signs appeared) Tugger was allowed to move back into the main cage with his cagemates. He looked great and gave the impression of once again being a very happy rat. The metronidazole was ceased from 10 June. The Buprenex was continued until 16 June, because Tugger appeared sore without it. The Baytril was continued for another month.

By 4 July 2012 Tugger was back to “98% super-normal rat play”. However, his keeper continued to watch for behaviours such as stopping abruptly when running about, which could indicate a twang of pain and possible tumor regrowth.

Unfortunately, in August Tugger began to decline, presumably due to effects of the cancer. The vet was consulted and Tugger’s keeper administered subcutaneous fluids. However, he continued to decline.

On 1 September Tugger was clearly not doing well and appeared to be “near the end”. His keeper spent all day holding and stroking him (which he sought out). Close to midnight he made it clear that he wanted to go into the hospital cage to be with his cage-mates. At 03:00 hours his keeper awoke him and he made a beeline to her to be held.

Tugger passed away (seemingly) peacefully on 2 September 2012 at 06:55 hrs.

Dr. Harvey’s notation and necropsy report:

-

“Tugger” did well post-operatively until 17 August, when he developed bright yellow urine, and subsequently jaundice. “Tugger” passed away on 2 September 2012 and a necropsy [see pathology report 2] was performed on 4 September.

Necropsy report as follows:

Necropsy report

HISTORY

Surgery to remove carcinoma at the tip of the cecum that had caused an intussusception

(in-folding) of the intestine and obstruction. Did well until recently when he slowed down and

became jaundiced. He died at home on 9/2/2012, The body was chilled until necropsy.

GROSS NECROPSY

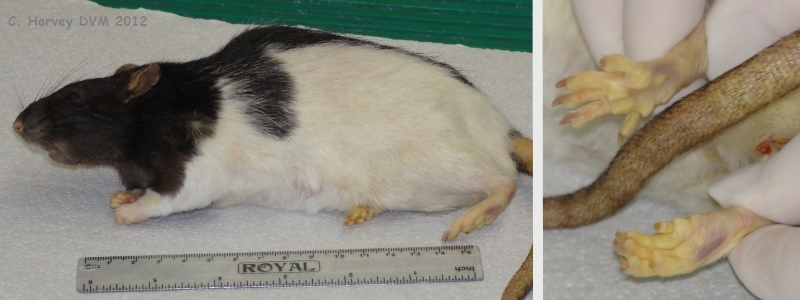

External: Moderate jaundice, most visible on feet. Fair body condition score. Coat normal. Skin

has some adherent orange flaking, normal for adult male rats.

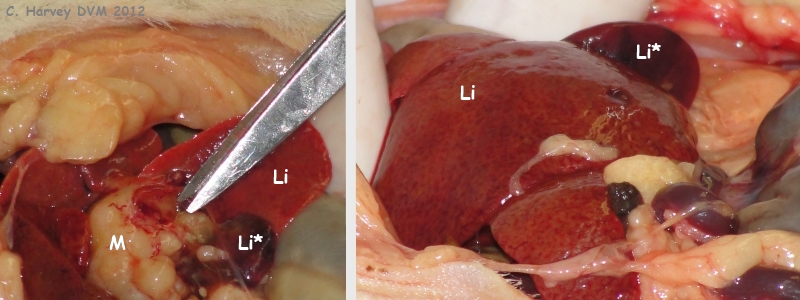

Abdomen: There is no free fluid in the abdomen. Stomach is normal, and full of food material. There is little ingesta in the Gl tract. No evidence of dilated intestine or obstruction. The remaining cecum appears normal, with no evide4nce of tumor regrowth. The dependent portion of the small intestine is dark red, likely due to post mortem settling of the blood. The mesentery (connective tissue supporting the intestine) is filled with small smooth firm whitish nodules ranging from 3-5 mm. The liver is mildly enlarged somewhat pale in color, and normal in size except the smallest lobe (possibly the caudate), which is darker and small. The area where the

bile ducts leave the liver to empty into the intestine is filled with a whitish firm irregular tissue mass similar to the nodule seen in the mesentery. Kidneys appear normal. The bladder surface has some petechiae (small areas of bleeding within the tissue). The urine is bright orange, not grossly bloody. The kidneys appear grossly normal. The spleen is at the upper limit of normal size, with the tail being somewhat thickened. There is a nodule on the serosal (outside) surface of the spleen similar to those seen in the mesentery.

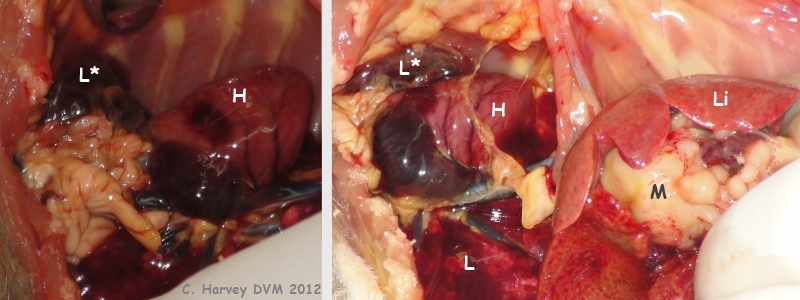

Chest: No free fluid. Heart grossly normal. Lungs appear somewhat collapsed, without obvious neoplasia.

The L caudal lung lobe is shrunken and dark, the cause is not apparent.

Assessment: Metastasis of previously removed cecal carcinoma to mesentery, causing physical obstruction of bile flow out of liver. Possible neoplastic infiltrate of spleen, and perhaps a solitary lobe of lung and liver. The small hemorrhages in the bladder and the dark color of the small intestine could indicate a paraneoplastic (secondary to cancer) bleeding problem, but that seems very unlikely.

Cause of death: No specific cause was found. It is likely that the cause of death was due to metabolic effects of the cancer. Medication was not likely a factor.

Photos

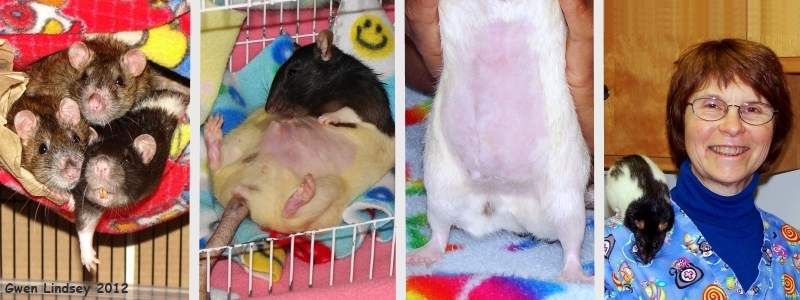

Left photo shows Tugger (r)with cage-mates before illness. Center two photos show Tugger healing following surgery. Last photo is of Dr. Harvey and her little patient “Tugger”. |

These photos were taken at the start of the necropsy. They show the moderate jaundice that was mostly visible on the feet. |

These photos show the opened up chest area and part of the abdominal area. The heart (H) is grossly normal. The lungs (L) appear somewhat collapsed, without obvious neoplasia. The left caudal lung lobe (L*) is shrunken and dark. A mass (M) is visible beneath the liver (Li). |

These photos show the opened up upper abdominal area. The liver (Li) is mildly enlarged and somewhat pale in colour. The smallest liver lobe (Li*, possibly the caudate) is darker and small. The area where the bile ducts leave the liver is filled with a whitish firm irregular tissue (M). |

These photos show the opened up abdominal area. The remaining cecum (C) appears normal, with no evidence of tumor regrowth. The dependent portion of the small intestine (I) is dark red, likely due to post mortem settling of the blood. The bladder surface (B) has some petechiae (small areas of bleeding within the tissue). The mesentery is indicated by “Me”. |

These photos show the mesentery, which is filled with small smooth firm whitish nodules ranging from 3-5 mm. |

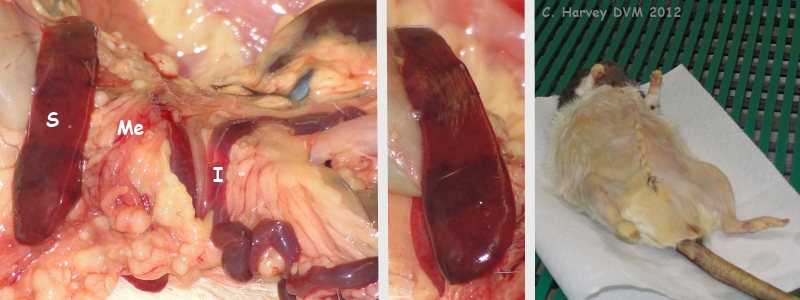

These photos provide another view of the mesentery (Me) and small intestine (I). They also show the spleen (S), which is at the upper limit of normal size, with the tail being somewhat thickened. There is a nodule (not shown) on the serosal (outside) surface of the spleen, similar to those seen in the mesentery. The last photo in this group shows closure following necropsy. |

Case history courtesy of: Gwen Lindsey

Case Editors: Karen Grant RN, Cyzahhe

Healthy and healing photos courtesy of: Gwen Lindsey, “JoinRats” https://www.joinrats.com

Surgical, post-op and follow-up notes, necropsy photos and report courtesy of: Carolynn Harvey, DVM

Histopathology report of removed mass courtesy of: Karen L. Oslund, DVM, Ph.D., Diplomate, American College of Veterinary Pathologists