Figure 3: Urolithiasis in 8-month-old neutered male rat. Multifocal abdominal abscesses identified in post mortem histopathology. (Gambit)

Case history, video and photos

History

Gambit was born on 27 October 2010. His father is presumed to be a wild Rattus norvegicus. His mother and two additional female rats were impregnated while living in a sewer system; they gave birth at a rat rescue.

All the semi-wild male pups were castrated at an early age (6 weeks) to increase their chances of finding homes and to prevent hormonal aggression. Gambit developed an abscess right-cranially to his penis on day 26 post-op. It opened on day 35, he cleaned it himself, and by day 41 it had healed completely. Gambit’s cagemate Twix (born from one of the other female rats) and his brothers Boris (living with another caretaker) also developed abscesses in similar areas. Both healed well, although Boris’s abscess did return (and heal again) several months later.

Gambit and his cagemates are fed ad libitum, a combination of various dry rat mixes and lab blocks, as well as various “human food items”. Fresh water is available at all times.

Clinical Signs

On 2 July 2011 (at appr. 8 months old), early in the morning, Gambit is discovered sitting in a corner of the cage, hunched up with piloerection and quite unresponsive (for a semi-wild rat). About two hours later, he is examined by a veterinarian. By that time, he has perked up considerably and the veterinarian cannot feel (abdomen) or hear (chest) anything abnormal. Gambit’s caretaker blames his earlier behaviour on the low room temperature and his just having woken up.

During July/August/September Gambit stretches his lower abdomen quite oddly and with increasing frequency. No other abnormalities are noticed, apart from some minor upper respiratory noises (“sniffles” and sneezes). In September the lower left quadrant of Gambit’s abdomen is palpated; it feels hard and “lumpy”.

Diagnosis

On 21 September 2011 (at appr.11 months old) urinalysis by a veterinarian shows that Gambit has a severe case of urolithiasis: his urine contains many struvite crystals. The pH is 7.5. There is no blood in the urine.

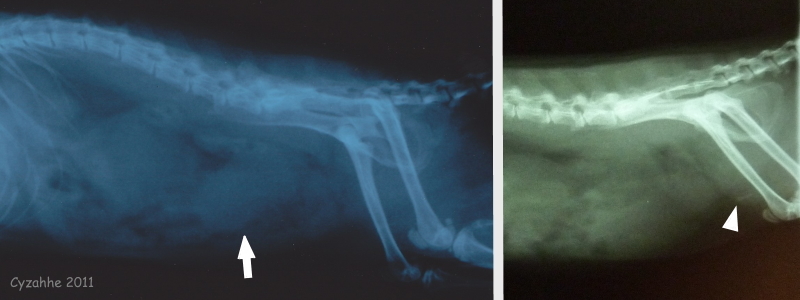

The lump that can be felt in Gambit’s abdomen is assumed by the veterinarian to be his enlarged and inflamed bladder. Note that an X-ray taken later (on 10 October) indeed shows a large “area” that is described by the veterinarian to be Gambit’s bladder. At the time, no urinary calculi are seen (note that these would need to be over 3mm in size in order for them to be picked up on X-ray). According to the veterinarian, Gambit does have “a calcified urethra, however this is most likely not painful” (note that rats have an os penis, which might have been mistakenly diagnosed as a calcified urethra!).

Treatment

Gambit as well as his cagemates’ staple diet is switched to Royal Canin Urinary S/O Canine Diet: dry kibble is fed ad libitum and twice a day they are given a bowl of meat with ample water. In addition, they are given crushed tablets of vitamin C (appr. 17mg/day) and cranberry (appr. 250mg/day), as well as fresh berries and berry juice.

Gambit is given Novacam (meloxicam) (0.05mg/kg) once a day against the pain. Sulfatrim Drops (40mg/kg) are given twice a day to prevent a urinary tract infection. Pro-Kolin+ and crushed vitamin B complex tablets are given one hour after the antibiotic to prevent diarrhea.

Follow-up

A follow-up urinalysis on 5 October shows obvious improvement: there are fewer crystals and they are smaller and rounder. The pH is now 6.5. There is a small amount of blood in the urine, possibly because Gambit’s bladder was massaged by the veterinarian to stimulate urination.

Gambit remains active and inquisitive. However, the odd stretching continues to the same degree and at the same frequency, even when the Novacam is given twice a day.

Outcome

On 16 October 2011 at 04:00 Gambit is discovered sitting in one of the semi-enclosed corner toilets in the cage, hunched up, with piloerection and clenched fists. He is lethargic and unresponsive. He drinks some water, but refuses to eat. His feces consists of yellow slime.

An emergency veterinarian is consulted. Assuming Gambit to be in sudden pain due to the urolithiasis, the Novacam dose is doubled. However, it does not appear to have any effect.

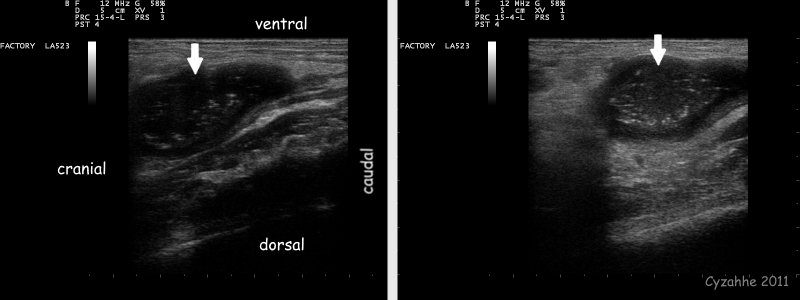

Later that Sunday (during what would be office hours on a workday), Gambit is taken to another emergency veterinarian, who performs an abdominal echo. No sedation is required, due to his lethargy. Several large lumps are discovered, which the veterinarian assumes to be (inoperable) tumours. Immediate euthanasia is advised.

Gambit is euthanized at 11 months of age.

Follow-up necropsy & histopathology

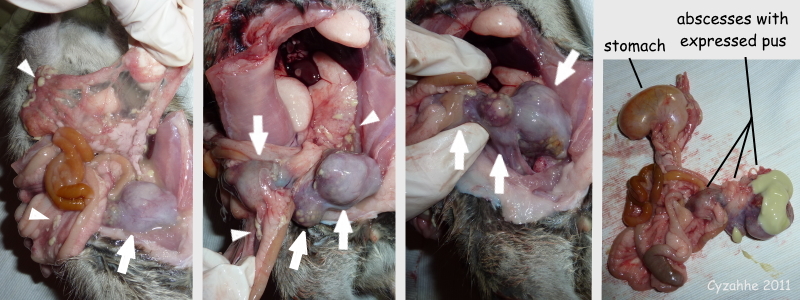

A necropsy is performed by Gambit’s caretaker 2.5 hours post-mortem (unrefrigerated). Tissue samples are collected and placed in formalin. Histopathology is performed a few weeks later. (Unfortunately, bacterial analysis could not be performed on the pus inside the lumps due to the formalin.)

MACROSCOPIC

Parts of the intestinal tract have adhered. Multifocal purulent sites surrounded by connective tissue. One site is at least 2cm in diameter.

MICROSCOPIC

Necropurulent sites with multifocal accumulations of bacteria, surrounded by thick connective tissue. Purulent sites within the connective tissue. An adjacent part of the intestinal tract has some plasma cells and heterophile granulocytes in its lamina propria. Lymphoplasma cellular infiltrates are present in other parts, in the direction of the serosa. Locally there is also some angiofibroblastic tissue.

CONCLUSION

Multifocal abscesses in and around the serosa of the intestine. No indication of neoplasia.

Summary

It is unclear how long the abdominal abscesses were present, whether the abscesses and urolithiasis were related, or which occurred first. Unfortunately, by the time the abdominal abscesses were recognized as such, they were too large and invasive, and Gambit was too weak, for surgery to be a viable option.

Interestingly, several months earlier, in March 2011, another semi-wild male born from one of the other female rats (and living with another caretaker) had been euthanized due to a sudden and rapid decline in wellbeing. When their veterinarian had performed a necropsy, adhesions had been discovered in the intestine, which, according to the veterinarian, contained “inflammation and tumours” (note that histopathology was not performed, so the presence of tumours is not certain). This male had not had a post-castration surgery abscess.

In February 2012, Gambit’s brother Boris (see History section above, he lived with another caretaker) also developed large lumps in his abdomen. Their veterinarian performed a laparoscopy, but concluded that the abscesses were too large, and the adhesions within the intestinal tract as well as to the peritoneum too severe, for surgery to be a viable option. Boris was euthanized. Histopathology showed that the pus inside the abscesses contained a large number of E.coli bacteria.

As Gambit’s cagemate Twix (see History section above) also displayed odd-looking stretching behaviour, though seemingly to a lesser degree, urinalysis (October 2011) and an abdominal echo (December 2011) were performed as a precaution; however, no abnormalities were found. Twix continued to live in good health, although he developed slowly progressing hind leg paresis and a pituitary tumour at an older age.

Photos and Videos

Video: This short video fragment shows an instance of the odd stretching (downwards arching of his back) Gambit displayed, as he walks down the stairs inside their cage.

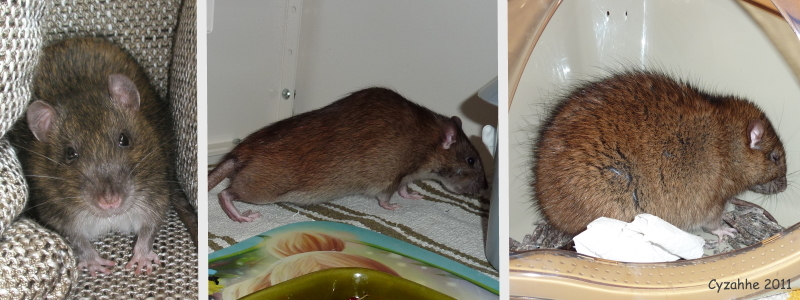

Row 01:The first photograph shows Gambit in April 2011, at 5 months of age. The second photograph was taken in late September and clearly shows the odd stretching. The final photograph was taken on the 16th of October, when he was found in pain and lethargic in the middle of the night; note the distinctive piloerection of his coat, and facial expression with closed eyes and lowered ears. |

Row 02:These two x-rays were taken by the primary veterinarian on the 10th of October 2011. The white arrow points to the (opaque) “area” that was thought to be the enlarged and inflamed bladder. The white arrowhead points to the os penis. |

Row 03:These slides are from the echo that was performed by the second emergency veterinarian on the 16th of October 2011. The white arrows point to the lumps that were diagnosed as “(inoperable) tumours”. |

Row 04:These photographs were taken during the necropsy that was performed by Gambit’s caretaker 2.5 hours post-mortem (unrefrigerated). The white arrows point to the large intestinal abscesses. Note that there are also bits of yellow-green pus scattered throughout the abdominal cavity (some of which is indicated by white arrowheads), possibly due to rupturing and subsequent leaking of one or more of the abscesses. In the final photograph the intestinal tract has been removed from the abdominal cavity and two of the abscesses have been cut open and the pus (partially) expressed. |

Full necropsy photos of Gambit’s condition can be viewed in Fig.2 under Necropsy Cases in the Health section of the Rat Guide.

Case history, photos and video courtesy of Cyzahhe

Necropsy performed by Cyzahhe

Histopathology (both for Gambit and Boris) by Utrecht University, Veterinary Pathology Diagnostic Centre (VPDC)